Ten ways to think better

by Seth Reynolds

edited by: Jan Jutten

Introduction

Never before have so many experienced global interdependence so strongly, so simultaneously and suddenly as they do now. Our responses to the threat of the coronavirus have triggered a flood of consequences thathave spread around the world faster than the virus. The reality of interdependence within systems has entered all of us in a very direct way at different levels: individually, administratively and in society as a whole.

The approach to the coronavirus will be studied for many years to come. We can learn many important lessons by putting on our system glasses.

The coronavirus has provided many examples of both effective system actions and actions where eachsystems approach was absent. All over the world, leaders and administrators are forced to think more broadly and deeply about causes and consequences. Decisions that are made, even words that are uttered without an awareness of how systems work, can wreak havoc.

Systems thinking, making well-considered plans, system actions and system leadership are now desperately needed: individually, in organizations, in society as a whole, both in the private and in the public sector. As oneAmerican diplomat recently put it: “From climate change to the coronavirus, complex adaptive systems thinking is key to handling crises”.

For many years, epidemiologists (one of the most important professions at the moment) have beenurging us to think and work more in favour of a systems approach. That still happens far too little. We do not think and act in accordance with how complex systems work, which became so strongly visible due to the corona crisis.

What are systems approaches?

Systems thinking goes beyond taking individual actions based on linear relationships between causes and effects.

In systems thinking, we need frameworks and tools that help us to better understand and act more effectively based on them. Systems do not exist “apart from ourselves”: we are part of them and we can influence them. The complexity ofsystems requires us to deal with uncertainty of the nonlinear, adaptive, self-organizing characteristics of systems.

Systems thinking is often seen as a kind of fringe phenomenon of people working in “a shelter of ambiguity”. However, complexity implies that multiple perspectives and interpretations are possible. System thinkers refer to this: there is no one truth. However, according to many, this approach does not help if an urgent crisis requires quickresponses and actions.

The cornonavirus shows how important systems thinking is. We will have to learn to think, act and organize from a systems approach. In doing so, we need processes, tools and technologies that can help us do so. That won’t always be easy. But if anything has become clear in recent weeks, it is that “continuing on the same path” is no longer possible and systems thinking is no longer just an option.

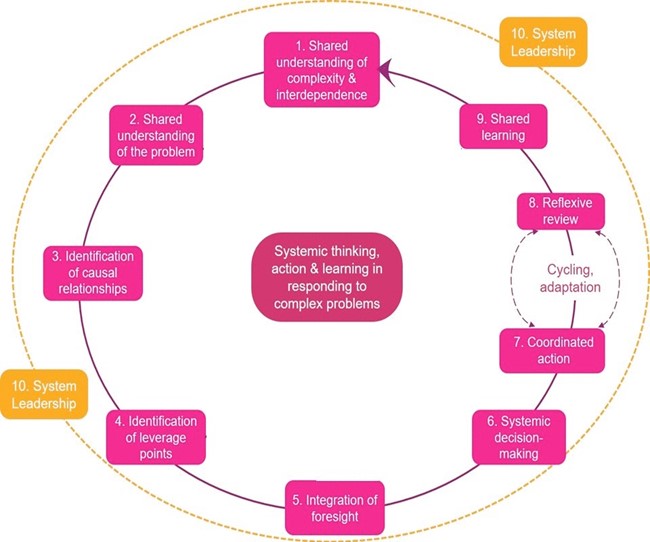

To underpin this approach,we have described the key components of systems thinking in more detail in this article. They are illustrated in the diagram below. It’s not a “how-to guide” to system change. The diagram shows an ideal picture, reality is rarelyarranged in this way. It provides a framework for a system change that can help us learn from the current crisis so that we can make better decisions in the future.

Ten ways to think better

1. A shared understanding of complexity and interdependence

Scientists indicate that we are happily unable to understand relationships and connections. They also call this “asystemic (or non-systemic) thinking”. This way of thinking has led to the fact that we have lost a lot of time in the corona crisis by reaging too late. This allowed the virus to spread for weeks. Unconscious biases played a role in this. Wuhan seemed very far away. Although this city in China is larger than London, most people had never heard of it. It is easy for peopleto imagine the connection between that city in China and its own environment. Yet Wuhan is one of the new Chinese mega-cities, with more than 500 international flights a day! There was therefore a 0% chance that the spread of the virus would be limited to this town. Our inability to see these connections has cost many thousands of lives.

If we really want to derive added value from systems thinking, it will have to be shared. We do not get any further withe nkele specialists who can do this well and the rest don’t. This was and still is one of the great challenges of systems thinking. How do we ensure that everyone learns this way of thinking?

Peter Senge indicates that children are naturally system thinkers, but that they unlearn it when they grow up in a world that thinks and works in a fragmented and linear way. In order to be able to act from a systems approach, we must be able to talk together about complexity, mutual dependency, how we experience it and, above all, about our own role in the systems around us. The coronavirus has been a great teacher at this point: it has hopefully created a new sense of urgency! Let us seize this opportunity to prevent further disasters in the future.

2. A shared understanding of the problem

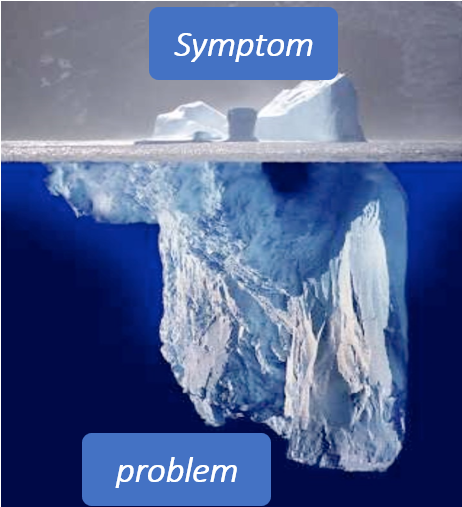

In addition to the joint better understanding of systems in general, it is also necessary to have a shared understanding of the specific problem. In many cases,we focus our attention on fighting symptoms rather than addressing the problem. By tackling problems such as climate change, effective actions are only possible if we have a common understanding of the nature of theproblem: understanding before intervention.

This was clearly not the case with the cornavirus. This allowed the virus to spread further and further while we humans were busy interpreting, discussing and arguing who was right. In America, a discussion even took place between the central government and the individual States. They only started to act when it was no longer possible to deny the problem. In Engelenad, too, people waited a very long time before taking action. On many plates,data and scientific consensus were ignored until the very last moment. In the end, almost all countries took roughly the same approach, albeit bit by bit.

The coronavirus shows how important it is that we understand togetherwhat is going on. In order to act effectively, it is necessary that the noses all point in the same direction. The invisible and highly contagious virus made everyone a player in the system and no longer a spectator. Anyone couldinfect others without being aware of it.

What makes systemic adversity so challenging is the fact that there are not only intellectual dimensions to it, but also emotionaland psychological aspects. These can prevent us from really understanding the problem. Arrogance and holding on to mental models from the past blind us from what then turns out to be irrefutable. Many spend too long declutteringand blaming others.

Large-scale problems such as these also require effective mass communication that ensures that people collectivelymisunderstand and understand the problem. The authorities in South Korea recognized the importance of this early on, and they carefully explained and broadly compromised the issue. These are all important lessons that we can apply everywhere if wewant to realize system changes. Jointly understanding the problem through clear communication and using unambiguous data that contribute to the understanding. Data is one of the most important allies in system change. With the coronavirus, just like with climate change, it turned out to be of great importance to show data very regularly.

3. Identifying causal relationships

Understanding and working with relationships is one of the essences of systems thinking. By using models such as causal loops, archetypes and the iceberg, we can visualize relationships. Causes and consequences that were previously still “hidden”, andwe are visible with these tools. The loops can then form the basis for conversations in which we look for other aspects that play a role or for possible interventions that can be effective. After we understand the problem, how can we best intervene?

The World Economic Forum has developed various schemes for this purpose. This mainly involves discovering mutual relationships in complex systems. That is an example.

With the coronavirus, we quickly saw the consequences that lockdown strategy has for things like domestic violence, the economy, loneliness, charities. Some of these consequences were already known and predictable based on existing data and models. If we succeed in further developing the system approach, we can integrate more and more data with the models we use. This allows us to predict and try to prevent more possible consequences.

4. Identifying leverage points

In a system approach, we look for levers: interventions that are very important and/or have the most impact on the operation of the system. This is also done with the help of the tools of systems thinking: models, mind maps, relationship circles and causal loops. Some examples of levers in the corona crisis:

- ensure that health care is not overloaded;

- ensuring adequate protective equipment for emergency workers;

- testing: detecting people whoare infected: they ensure that targeted effective interventions are possible without everyone being treated as infected (as is the case with a lockdown). This happened successfully in South Korea, Singapore and Hong Kong. In America and in Europe, people opted for a lockdown.

Without identifying the most important levers, it is not possible to successfully change systems

5. Foresight

Looking ahead can be integrated into a systems approach by looking at longer-term effects. It emphasizes that there are all kinds of possibilities on which the system develops further. As Meg Wheatley puts it, “You will never know what a system does when you do something to the system.” By better understanding together, we can take actions that have the most desired effects. With the coronavirus, we see several examples of too little attention for the longer term. Wuhan, for example, was the center of face mask production. Due to the virus, the region was the first in a lockdown. This had been warned about before, but it was ignored. In America, an organization dedicated to preventing pandemics was closed last year.

This also applies to the way in which one America is trying to fight the coronavirus in prisons. The data from other countries and people knew what was needed (such as suspending the prison sentence, releasing vulnerable and non-dangerous detainees early). Yet this was only done after great pressure from experts and even now it is still happening sparsely. This has caused many hundreds of prisoners tolive crazy. Of course it’s easy to talk afterwards (if only we had…..). Overseeing longer-term consequences is not always easy. By working together to find out about this thinking, not looking for culprits and by making better use of data , a lot of mischief can be prevented.

6. Systemic decision-making

If we bring all of the above together, we are better able to go further than just focusing on incidents, on thesymptoms of a problem. With the help of systems thinking, we look for relationships and connections, for levers that are effective, we look at possible consequences in the longer term. In short: we increase our place and time horizon: what we do here has consequences in other places. What you do now has consequences for the future.

The problems that are now going to play a role in the Charities and charity are an example of how much we need the systems approachand in making wise decisions. Think, for example, of food banks and facilities for the homeless. Half of all charities fear they will not be able to survive in the next six months if there is no financial support. This has majo rconsequences for vulnerable people who urgently need their help.

7. Coordinated action

A systems approach requires strong coordination between various sectors and stakeholders. This applies not only to a cris, but to all complex problems. There is often fragmentation, in which everyone focuses only on one part of the problem. We will have to cooperate more with other stakeholders in the system, often with people from very differentsectors than we are in ourselves.

For many, this means a completely different way of working than what one is used to.

8. Reflexive review

In many situations, a cycle of action-evaluation-learning preparation is alreadyin place. Most complex systems are characterized by their dynamics and adaptivity. This is also required of us in a systems approach. It asks us not only to look back linearly on cause-effect relationships. It is necessary to be reflective: a continuous and cyclical process of conscious reflection, individually and collectively. We need to be constantly aware of our actions and their impact on our systems. Many of us willreflect on our own reactions to the coronavirus during the corona crisis:

- did I perhaps participate in hoarding that created a shortage for vulnerable people?

- have I kept enough distance?

- did I stay at home as much as possible?

- did I perhaps infect people without my knowledge?

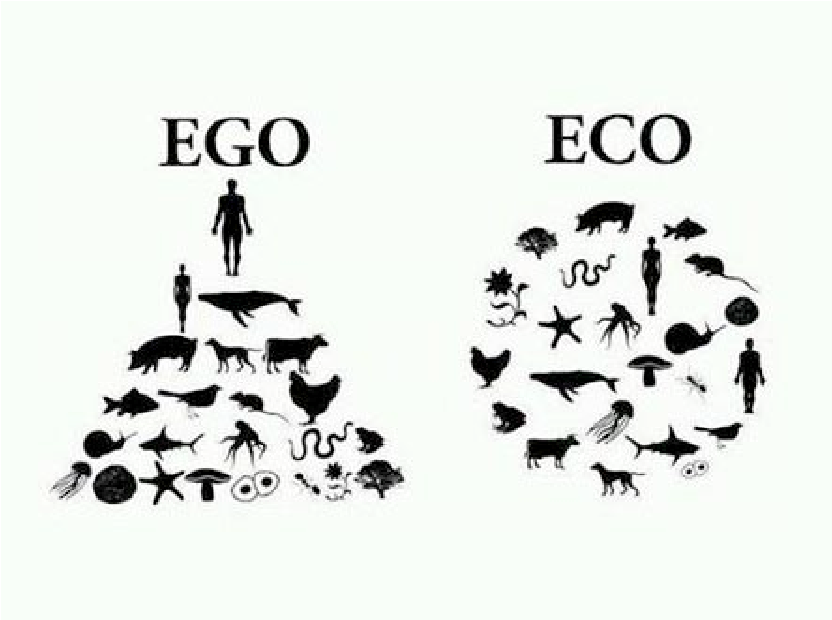

We now have the opportunity to reflect on the role we play in the development of systems. Let’s think about what we do, how we do things and especially why we do things. Is there an ego or an eco-approach? Do we do things because they have to or because they matter?

9. Shared learning

In a systems approach, learning is not limited to academics and professionals. Everyone learns with and from each other to continuously and sustainably improve the systems of which they belong. This can be done, among other things, through collective reflection: “the system must be able to see itself.” What are we doing? What is the impact of our behavior on the system? Is that what we all want? What adjustments are needed? How can we prevent fouten in the future?

In the example of the corona crisis: how can we ensure that we respond more adequately to the next pandemic? One of the reasons why South Korea and Singapore responded more quickly and better to the coronaviruscrisis is the fact that the SARS epidemic was still fresh in the memory in 2003.

10. System leadership

To enable the above system approach, system leadership is necessary. This term is used by Peter Senge, among others. He defines system leadership as the ability to act effectively in a complex system. Some characteristics that are needed for this: insight into the whole, being able to look at problems from different perspectives, listening well, conducting dialogue, inspiring, connecting, supporting, creating space to learn from each other, modesty, transparency, stimulating joint responsibility.

During the corona crisis, we saw many examples of lack of these characteristics of system leadership. We see leaders who point to blame, who cause division, who act too late or not at all. The experiences we are gaining now can form the basis for a different approach in the coming years. Organizational development experts put it this way: “The same disruption can have a very different impact on different organizations, depending on how the leaders within that organization are with dealing with the situation.”

What we can learn from the corona crisis is that we need systems thinking and system leadership. Leadership with the ability to restart and rebuild organizations, sectors and our society.

Systems thinking is no longer optional, it’s a moral purpose!